In the old Lenin shipyard in Gdansk, where striking workers were once the catalyst for major political change, young Poles now debate how to protect democracy in their country.

They worry that the rights and freedoms won by the Solidarity movement over three decades ago are at risk, as the ruling right-wing Law and Justice party, or PiS, campaigns to secure a record third term in office.

"It's a very important election. We're deciding whether we're going back to being a democratic country," was student activist Julia Landowska's stark take on this weekend's vote.

"This is our last call, to go to the election and fight for a better future in Poland."

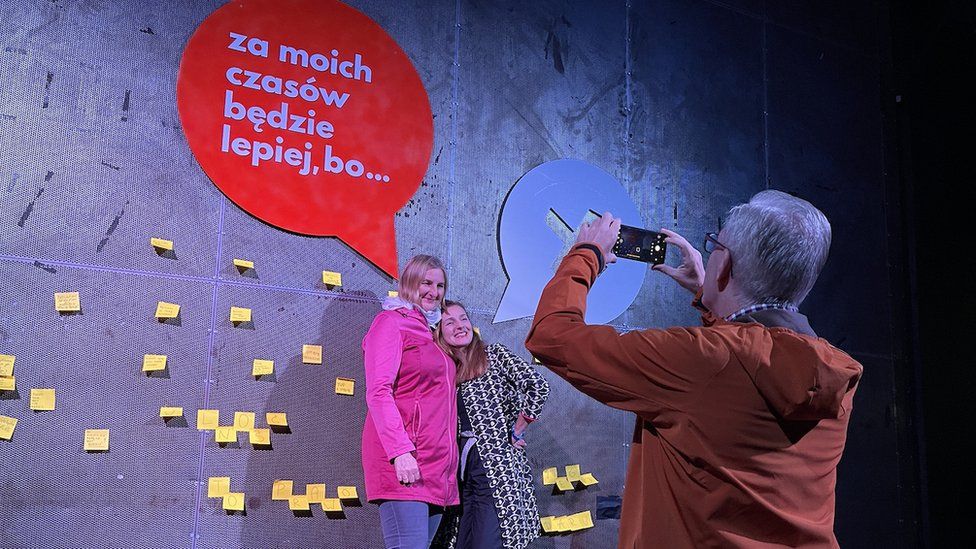

The event she helped organise was held under the slogan In My Day, Things Will Be Better.

A mixture of discussions and live music topped off with a silent disco, it was designed to encourage reluctant younger voters to the polls.

The activist's worries are echoed by others in Gdansk, who point to the shrinking independence of the courts under a PiS government and backsliding on women's rights, including a near-total ban on abortion.

There is also concern about media freedom - publicly-funded TV becoming a government mouthpiece - as well as acrimonious wrangling with Brussels on issues from judicial reform to migration.

That is why many Poles are now hailing the election on 15 October as the most important since 1989, when Solidarity candidates swept the board in the first partially-free vote since communist rule.

Freedom City

The story of Poland's struggle for freedom dominates the northern port city of Gdansk.

There is a Solidarity museum in the shipyard once occupied by strikers and billboards through the city centre that recount the momentous changes brought by their protest, led by an electrician named Lech Walesa.

This year, his son is running for re-election.

"We have to make sure we win, to reform all that has been destroyed in eight years," Jaroslaw Walesa explained, referring to the two terms PiS have held office so far.

Representing the opposition Civil Coalition, like fellow Gdansk-native and party leader Donald Tusk, he is most worried by Poland's increasingly antagonistic relations with the EU.

Like Brussels, he is also concerned about the politicisation of Polish courts.

"If you look at what has been done to our democracy, we took a huge step backwards. That's definitely not what my father fought for," Mr Walesa told the BBC this week, wandering the paths of the handsome Oliwki park, greeting voters with leaflets and a promise of change.

The 1989 slogan - Don't sleep, or they'll outvote you! - has been resurrected in Gdansk for this election, all part of pitching it as another critical moment for Polish democracy.

The city is expected to vote solidly for the opposition, as usual.

But opinion polls put the governing Law and Justice Party ahead nationwide, although probably without a big enough majority to form a government.

So the last-minute battle for votes is intense.

PiS and Security

In the town of Elblag, a short drive from Gdansk, campaigners spent Saturday canvassing for the governing party at a food market.

Between piles of potatoes and giant pumpkins, they dished out bags printed with the PiS logo and leaflets promoting the city's main candidate, who didn't show up.

"PiS have a good programme for us young people and for my children. I have twins and they've got a good programme for our future," party activist Monica explained, referring to the 500 zloty (£95) monthly child benefit the government now pays.

It is set to rise to 800 next year if PiS win.

"In Poland, this amount can solve many things," her husband added.

Neither accepted the opposition's fears for the future of democracy in Poland. "Democracy is good for us," Monica said - and she wants to stay in the EU.

The pair both talked about security, including the government's slogan that it is "protecting the future of Poles".

"We're not ready to accept immigrants. Muslims," Monica clarified, adding that Poland had already taken in "a lot of Ukrainians", meaning those who came in 2022 as refugees.

The Russian exclave of Kaliningrad is nearby and there is a new barbed-wire fence along its entire length.

The activists' pro-government message was not universally welcomed by marketgoers, even though the Elblag regional vote was strongly pro-PiS at the last election.

Several shoppers thrust the free bags back when they realised which party logo was printed on them. Others retorted that PiS had been so good for Poland that their children had moved abroad for better opportunities.

Nasty talk

In such a polarised race, much of the campaigning has been nasty.

In this week's testy election debate on state TV, Donald Tusk again referred to the government as "evil" and called the prime minister Pinocchio.

PM Mateusz Morawiecki shrugged him, and others, off as a "band of redheads", in reference to Mr Tusk's hair. His party consistently claims that the Civic Coalition represents "foreign interests", painting Donald Tusk as a traitor and a stooge of Berlin.

Such talk is particularly worrying in Gdansk.

Piotr Adamowicz tells me he gets heckled at election events, usually by elderly voters who yell that he is "German" and should "speak Polish".

"The current campaign is very aggressive, from the tongues of politicians and state media, and it is very dangerous," the Civic Coalition candidate says.

It is a statement he does not make lightly: his brother, Pawel, the former mayor of Gdansk, was fatally stabbed on stage in 2019.

The murderer, who had just been released from prison, falsely claimed that "Civic Platform tortured me".

"The disgusting politics and hate speech [we see now] hurts and worries me because such a tragedy could happen again," Piotr Adamowicz warns.

He says he regularly gets anonymous death threats including promises to "stab you like your brother".

Protest vote

Back in the shadow of the giant cranes at the old Lenin shipyard, young people posed in front of a sign declaring how they want to improve their country.

"We're really worried. That's why we came: so we can change something," first-year psychology student Julia explained.

She pointed to the near ban on abortion that sparked giant protests in 2020 as one of her big concerns.

"If the governing party wins, I will maybe just leave the country, it's that bad!" added Sophia, a gay woman distressed by the introduction of "LGBT-free zones" some years ago, several of which remain in place.

"They hate me! I'm scared."

Both 20-year-olds were shocked by the rhetoric at this, their first ever election. "Everyone is fuming and it's kind of scary!" Sophia said.

Two years ago, event organiser Julia Landowska was fined for swearing about PiS at a protest, a charge she is currently appealing.

She believes her case was meant to frighten others and silence dissent.

So as PiS supporters are encouraged to the polls by talk of more security and more social spending, Julia plans to cast her own vote for change - less momentous than in 1989, but important.

"Step by step, they are taking more and more away from us," she argued.

"We believe this election can change many things in Poland. So it's important to go and vote and decide about our future."

Post a Comment